The Go Optimizations 101 and

Go Details & Tips 101 books

have been updated to Go 1.25.

The most cost-effective way to get them is through

this book bundle

in the Leanpub book store.

If you would like to learn some Go details and facts every serveral days, please follow @zigo_101.

Code Blocks and Identifier Scopes

This article will explain the code blocks and identifier scopes in Go.

(Please note, the definitions of code block hierarchies in this article are a little different from the viewpoint of

go/* standard packages.)

Code Blocks

In a Go project, there are four kinds of code blocks (also called blocks later):

-

the universe block contains all project source code.

-

each package has a package block containing all source code, excluding the package import declarations in that package.

-

each file has a file block containing all the source code, including the package import declarations, in that file.

-

generally, a pair of braces

{}encloses a local block. However, some local blocks aren't enclosed within{}, such blocks are called implicit local blocks. The local blocks enclosed in{}are called explicit local blocks. The{}in composite literals and type definitions don't form local blocks.

Some keywords in all kinds of control flows are followed by some implicit code blocks.

-

An

if,switchorforkeyword is followed by two nested local blocks. One is implicit, the other is explicit. The explicit one is nested in the implicit one. If such a keyword is followed by a short variable declaration, then the variables are declared in the implicit block. -

An

elsekeyword is followed by one explicit or implicit block, which is nested in the implicit block following itsifcounterpart keyword. If theelsekeyword is followed by anotherifkeyword, then the code block following theelsekeyword can be implicit, otherwise, the code block must be explicit. -

An

selectkeyword is followed by one explicit block. -

Each

caseanddefaultkeyword is followed by one implicit block, which is nested in the explicit block following its correspondingswitchorselectkeyword.

The local blocks which aren't nested in any other local blocks are called top-level (or package-level) local blocks. Top-level local blocks are all function bodies.

Note, the input parameters and output results of a function are viewed as being declared in explicit body code block of the function, even if their declarations stay out of the pair of braces enclosing the function body block.

Code block hierarchies:

-

package blocks are nested in the universe block.

-

file blocks are also directly nested in the universe block, instead of package blocks. (This explanation is different from the

go/*standard packages.) -

each top-level local block is nested in both a package block and a file block. (This explanation is also different from the

go/*standard packages.) -

a non-top local block must be nested in another local block.

(The differences to Go specification are to make the below explanations for identifier shadowing simpler.)

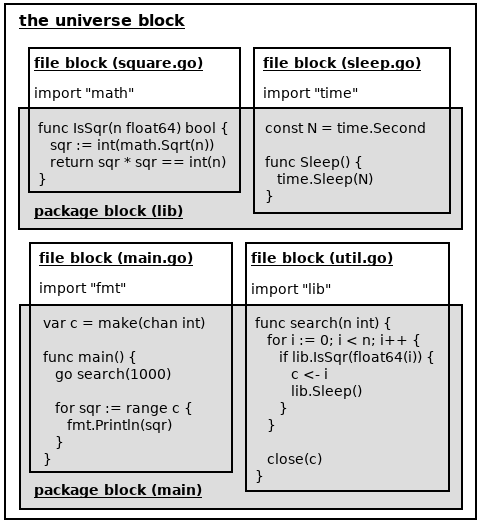

Here is a picture shows the block hierarchies in a program:

Code blocks are mainly used to explain allowed declaration positions and scopes of source code element identifiers.

Source Code Element Declaration Places

There are six kinds of source code elements which can be declared:

-

package imports.

-

defined types and type alias.

-

named constants.

-

variables.

-

functions.

-

labels.

Labels are used in the

break, continue, and goto statements.

A declaration binds a non-blank identifier to a source code element (constant, type, variable, function, label, or package). In other words, in the declaration, the declared source code element is named as the non-blank identifier. After the declaration, we can use the non-blank identifier to represent the declared source code element.

The following table shows which code blocks all kinds of source code elements can be directly declared in:

| the universe block | package blocks | file blocks | local blocks | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| predeclared (built-in elements) (1) |

Yes

|

|

|

|

| package imports |

|

|

Yes

|

|

| defined types and type alias (non-builtin) |

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

| named constants (non-builtin) |

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

| variables (non-builtin) (2) |

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

| functions (non-builtin) |

|

Yes

|

Yes

|

|

| variables (non-builtin) (2) |

|

|

|

Yes

|

(1) predeclared elements are documented in

(2) excluding struct field variables.

builtin standard package.(2) excluding struct field variables.

So,

-

package imports can never be declared in package blocks and local blocks.

-

functions can never be declared in local blocks. (Anonymous functions can be enclosed in local blocks but they are not declarations.)

-

labels can only be declared in local blocks.

Please note,

-

if the innermost containing blocks of two code element declarations are the same one, then the names (identifiers) of the two code elements can't be identical.

-

the name (identifier) of a package-level code element declared in a package must not be identical to any package import name declared in any source file in the package (a.k.a., a package import name in a package must not be identical to any package-level code element declared in the package). This rule might be relaxed later.

-

if the innermost containing function body blocks of two label declarations are the same one, then the names (identifiers) of the two labels can't be identical.

-

the references of a label must be within the innermost function body block containing the declaration of the label.

-

some special portions in the implicit local blocks in all kinds of control flows have special requirements. Generally, no code elements are allowed to be directly declared in such implicit local blocks, except some short variable declarations.

-

Each

if,switchorforkeyword can be closely followed by a short variable declaration. -

Each

casekeyword in aselectcontrol flow can be closely followed by a short variable declaration.

-

(BTW, the

go/* standard packages think file code blocks can only contain package import declarations.)

The source code elements declared in package blocks but outside of any local blocks are called package-level source code elements. Package-level source code elements can be named constants, variables, functions, defined types, or type aliases.

Scopes of Declared Source Code Elements

The scope of a declared identifier means the identifiable range of the identifier (or visible range).

Without considering identifier shadowing which will be explained in the last section of the current article, the scope definitions for the identifiers of all kinds of source code elements are listed below.

-

The scope of a predeclared/built-in identifier is the universe block.

-

The scope of the identifier of a package import is the file block containing the package import declaration.

-

The scope of an identifier denoting a constant, type, variable, or function (but not method) declared at package level is the package block.

-

The scope of an identifier denoting a method receiver, function parameter, or result variable is the corresponding function body (a local block).

-

The scope of the identifier of a constant or a variable declared inside a function body begins at the end of the specification of the constant or variable (or the end of the declaration for a short declared variable) and ends at the end of the innermost containing block.

-

The scope of the identifier of a type or a type alias declared inside a function body begins at the end of the identifier in the corresponding type specification and ends at the end of the innermost containing block.

-

The scope of a label is the body of the innermost function body block containing the label declaration but excludes all the bodies of anonymous functions nested in the containing function.

-

About the scopes of type parameters, please read the Go generics 101 book.

Blank identifiers have no scopes.

(Note, the predeclared

iota is only visible in constant declarations.)

You may have noticed the minor difference of identifier scope definitions between local type definitions and local variables, local constants and local type aliases. The difference means a defined type may be able to reference itself in its declaration. Here is an example to show the difference.

package main

func main() {

// var v int = v // error: v is undefined

// const C int = C // error: C is undefined

/*

type T = struct {

*T // error: T uses <T>

x []T // error: T uses <T>

}

*/

// Following type definitions are all valid.

type T struct {

*T

x []T

}

type A [5]*A

type S []S

type M map[int]M

type F func(F) F

type Ch chan Ch

type P *P

// ...

var p P

p = &p

p = ***********************p

***********************p = p

var s = make(S, 3)

s[0] = s

s = s[0][0][0][0][0][0][0][0]

var m = M{}

m[1] = m

m = m[1][1][1][1][1][1][1][1]

}

Note, call

fmt.Print(s) and call fmt.Print(m) both panic (for stack overflow).

And the scope difference between package-level and local declarations:

package main

// Here the two identifiers at each line are the

// same one. The right ones are both not the

// predeclared identifiers. Instead, they are

// same as respective left one. So the two

// lines both fail to compile.

/*

const iota = iota // error: constant definition loop

var true = true // error: typechecking loop

*/

var a = b // can reference variables declared later

var b = 123

func main() {

// The identifiers at the right side in the

// next two lines are the predeclared ones.

const iota = iota // ok

var true = true // ok

_ = true

// The following lines fail to compile, for

// c references a later declared variable d.

/*

var c = d

var d = 123

_ = c

*/

}

Identifier Shadowing

Ignoring labels, an identifier declared in an outer code block can be shadowed by the same identifier declared in code blocks nested (directly or indirectly) in the outer code block.

Labels can’t be shadowed.

If an identifier is shadowed, its scope will exclude the scopes of its shadowing identifiers.

Below is an interesting example. The code contains 6 declared variables named

x. A x declared in a deeper block shadows the xs declared in shallower blocks.

package main

import "fmt"

var p0, p1, p2, p3, p4, p5 *int

var x = 9999 // x#0

func main() {

p0 = &x

var x = 888 // x#1

p1 = &x

for x := 70; x < 77; x++ { // x#2

p2 = &x

x := x - 70 // // x#3

p3 = &x

if x := x - 3; x > 0 { // x#4

p4 = &x

x := -x // x#5

p5 = &x

}

}

// 9999 888 77 6 3 -3

fmt.Println(*p0, *p1, *p2, *p3, *p4, *p5)

}

Another example: the following program prints

Sheep Goat instead of Sheep Sheep. Please read the comments for explanations.

package main

import "fmt"

var f = func(b bool) {

fmt.Print("Goat")

}

func main() {

var f = func(b bool) {

fmt.Print("Sheep")

if b {

fmt.Print(" ")

f(!b) // The f is the package-level f.

}

}

f(true) // The f is the local f.

}

If we modify the above program as the following shown, then it will print

Sheep Sheep.

func main() {

var f func(b bool)

f = func(b bool) {

fmt.Print("Sheep")

if b {

fmt.Print(" ")

f(!b) // The f is also the local f now.

}

}

f(true)

}

For some circumstances, when identifiers are shadowed by variables declared with short variable declarations, some new gophers may get confused about whether a variable in a short variable declaration is redeclared or newly declared. The following example (which has bugs) shows the famous trap in Go. Almost every gopher has ever fallen into the trap in the early days of using Go.

package main

import "fmt"

import "strconv"

func parseInt(s string) (int, error) {

n, err := strconv.Atoi(s)

if err != nil {

// Some new gophers may think err is an

// already declared variable in the following

// short variable declaration. However, both

// b and err are new declared here actually.

// The new declared err variable shadows the

// err variable declared above.

b, err := strconv.ParseBool(s)

if err != nil {

return 0, err

}

// If execution goes here, some new gophers

// might expect a nil error will be returned.

// But in fact, the outer non-nil error will

// be returned instead, for the scope of the

// inner err variable ends at the end of the

// outer if-clause.

if b {

n = 1

}

}

return n, err

}

func main() {

fmt.Println(parseInt("TRUE"))

}

The output:

1 strconv.Atoi: parsing "TRUE": invalid syntax

Go only has 25 keywords. Keywords can't be used as identifiers. Many familiar words in Go are not keywords, such as

int, bool, string, len, cap, nil, etc. They are just predeclared (built-in) identifiers. These predeclared identifiers are declared in the universe block, so custom declared identifiers can shadow them. Here is a weird example in which many predeclared identifiers are shadowed. Its compiles and runs okay.

package main

import (

"fmt"

)

// Shadows the built-in function identifier "len".

const len = 3

// Shadows the built-in const identifier "true".

var true = 0

// Shadows the built-in variable identifier "nil".

type nil struct {}

// Shadows the built-in type identifier "int".

func int(){}

func main() {

fmt.Println("a weird program")

var output = fmt.Println

// Shadows the package import "fmt".

var fmt = [len]nil{{}, {}, {}}

// Sorry, "len" is a constant.

// var n = len(fmt)

// Use the built-in cap function instead, :(

var n = cap(fmt)

// The "for" keyword is followed by one

// implicit local code block and one explicit

// local code block. The iteration variable

// "true" shadows the package-level variable

// "true" declared above.

for true := 0; true < n; true++ {

// Shadows the built-in const "false".

var false = fmt[true]

// The new declared "true" variable

// shadows the iteration variable "true".

var true = true+1

// Sorry, "fmt" is an array, not a package.

// fmt.Println(true, false)

output(true, false)

}

}

The output:

a weird program

1 {}

2 {}

3 {}

Yes, this example is extreme. It contains many bad practices. Identifier shadowing is useful, but please don't abuse it.

The Go 101 project is hosted on GitHub. Welcome to improve Go 101 articles by submitting corrections for all kinds of mistakes, such as typos, grammar errors, wording inaccuracies, description flaws, code bugs and broken links.

The digital versions of this book are available at the following places:

- Leanpub store, $19.99+ (You can get this book from this boundle which also contains 3 other books, with the same price).

- Amazon Kindle store, (unavailable currently).

- Apple Books store, $19.99.

- Google Play store, $19.99.

- Free ebooks, including pdf, epub and azw3 formats.

Tapir, the author of Go 101, has been on writing the Go 101 series books since 2016 July.

New contents will be continually added to the books (and the go101.org website) from time to time.

Tapir is also an indie game developer.

You can also support Go 101 by playing Tapir's games:

Individual donations via PayPal are also welcome.- Color Infection (★★★★★), a physics based original casual puzzle game. 140+ levels.

- Rectangle Pushers (★★★★★), an original casual puzzle game. Two modes, 104+ levels.

- Let's Play With Particles, a casual action original game. Three mini games are included.

Articles in this book:

- About Go 101 - why this book is written.

- Acknowledgments

- An Introduction of Go - why Go is worth learning.

- The Go Toolchain - how to compile and run Go programs.

-

Become Familiar With Go Code

- Introduction of Source Code Elements

- Keywords and Identifiers

- Basic Types and Their Value Literals

- Constants and Variables - also introduces untyped values and type deductions.

- Common Operators - also introduces more type deduction rules.

- Function Declarations and Calls

- Code Packages and Package Imports

- Expressions, Statements and Simple Statements

- Basic Control Flows

- Goroutines, Deferred Function Calls and Panic/Recover

-

Go Type System

- Go Type System Overview - a must read to master Go programming.

- Pointers

- Structs

- Value Parts - to gain a deeper understanding into Go values.

- Arrays, Slices and Maps - first-class citizen container types.

- Strings

- Functions - function types and values, including variadic functions.

- Channels - the Go way to do concurrency synchronizations.

- Methods

- Interfaces - value boxes used to do reflection and polymorphism.

- Type Embedding - type extension in the Go way.

- Type-Unsafe Pointers

- Generics - use and read composite types

- Reflections - the

reflectstandard package.

-

Some Special Topics

- Line Break Rules

- More About Deferred Function Calls

- Some Panic/Recover Use Cases

- Explain Panic/Recover Mechanism in Detail - also explains exiting phases of function calls.

- Code Blocks and Identifier Scopes

- Expression Evaluation Orders

- Value Copy Costs in Go

- Bounds Check Elimination

-

Concurrent Programming

- Concurrency Synchronization Overview

- Channel Use Cases

- How to Gracefully Close Channels

- Other Concurrency Synchronization Techniques - the

syncstandard package. - Atomic Operations - the

sync/atomicstandard package. - Memory Order Guarantees in Go

- Common Concurrent Programming Mistakes

- Memory Related

- Some Summaries