The Go Optimizations 101 and

Go Details & Tips 101 books

have been updated to Go 1.25.

The most cost-effective way to get them is through

this book bundle

in the Leanpub book store.

If you would like to learn some Go details and facts every serveral days, please follow @zigo_101.

Goroutines, Deferred Function Calls and Panic/Recover

This article will introduce goroutines and deferred function calls. Goroutine and deferred function call are two unique features in Go. This article also explains panic and recover mechanism. Not all knowledge relating to these features is covered in this article, more will be introduced in future articles.

Goroutines

Modern CPUs often have multiple cores, and some CPU cores support hyper-threading. In other words, modern CPUs can process multiple instruction pipelines simultaneously. To fully use the power of modern CPUs, we need to do concurrent programming in coding our programs.

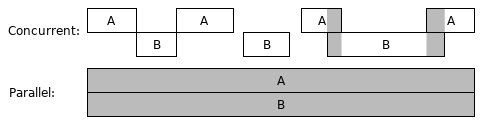

Concurrent computing is a form of computing in which several computations are executed during overlapping time periods. The following picture depicts two concurrent computing cases. In the picture, A and B represent two separate computations. The second case is also called parallel computing, which is special concurrent computing. In the first case, A and B are only in parallel during a small piece of time.

Concurrent computing may happen in a program, a computer, or a network. In Go 101, we only talk about program-scope concurrent computing. Goroutine is the Go way to create concurrent computations in Go programming.

Goroutines are also often called green threads. Green threads are maintained and scheduled by the language runtime instead of the operating systems. The cost of memory consumption and context switching, of a goroutine is much lesser than an OS thread. So, it is not a problem for a Go program to maintain tens of thousands goroutines at the same time, as long as the system memory is sufficient.

Go doesn't support the creation of system threads in user code. So, using goroutines is the only way to do (program scope) concurrent programming in Go.

Each Go program starts with only one goroutine, we call it the main goroutine. A goroutine can create new goroutines. It is super easy to create a new goroutine in Go, just use the keyword

go followed by a function call. The function call will then be executed in a newly created goroutine. The newly created goroutine will exit alongside the exit of the called function.

All the result values of a goroutine function call (if the called function returns values) must be discarded in the function call statement. The following is an example which creates two new goroutines in the main goroutine. In the example,

time.Duration is a custom type defined in the time standard package. Its underlying type is the built-in type int64. Underlying types will be explained in the next article.

package main

import (

"log"

"math/rand"

"time"

)

func SayGreetings(greeting string, times int) {

for i := 0; i < times; i++ {

log.Println(greeting)

d := time.Second * time.Duration(rand.Intn(5)) / 2

time.Sleep(d) // sleep for 0 to 2.5 seconds

}

}

func main() {

log.SetFlags(0)

go SayGreetings("hi!", 10)

go SayGreetings("hello!", 10)

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

}

Quite easy. Right? We do concurrent programming now! The above program may have three user-created goroutines running simultaneously at its peak during run time. Let's run it. One possible output result:

hi! hello! hello! hello! hello! hi!

When the main goroutine exits, the whole program also exits, even if there are still some other goroutines which have not exited yet.

Unlike previous articles, this program uses the

Println function in the log standard package instead of the corresponding function in the fmt standard package. The reason is the print functions in the log standard package are synchronized (the next section will explain what synchronizations are), so the texts printed by the two goroutines will not be messed up in one line (though the chance of the printed texts being messed up by using the print functions in the fmt standard package is very small for this specific program).

Concurrency Synchronization

Concurrent computations may share resources, generally memory resource. The following are some circumstances that may occur during concurrent computing:

-

In the same period that one computation is writing data to a memory segment, another computation is reading data from the same memory segment. Then the integrity of the data read by the other computation might be not preserved.

-

In the same period that one computation is writing data to a memory segment, another computation is also writing data to the same memory segment. Then the integrity of the data stored at the memory segment might be not preserved.

These circumstances are called data races. One of the duties in concurrent programming is to control resource sharing among concurrent computations, so that data races will never happen. The ways to implement this duty are called concurrency synchronizations, or data synchronizations, which will be introduced one by one in later Go 101 articles.

Other duties in concurrent programming include

-

determine how many computations are needed.

-

determine when to start, block, unblock and end a computation.

-

determine how to distribute workload among concurrent computations.

The program shown in the last section is not perfect. The two new goroutines are intended to print ten greetings each. However, the main goroutine will exit in two seconds, so many greetings don't have a chance to get printed. How to let the main goroutine know when the two new goroutines have both finished their tasks? We must use something called concurrency synchronization techniques.

Go supports several concurrency synchronization techniques. Among them, the channel technique is the most unique and popularly used one. However, for simplicity, here we will use another technique, the

WaitGroup type in the sync standard package, to synchronize the executions between the two new goroutines and the main goroutine.

The

WaitGroup type has three methods (special functions, will be explained later): Add, Done and Wait. This type will be explained in detail later in another article. Here we can simply think

-

the

Addmethod is used to register the number of new tasks. -

the

Donemethod is used to notify that a task is finished. -

and the

Waitmethod makes the caller goroutine become blocking until all registered tasks are finished.

Example:

package main

import (

"log"

"math/rand"

"time"

"sync"

)

var wg sync.WaitGroup

func SayGreetings(greeting string, times int) {

for i := 0; i < times; i++ {

log.Println(greeting)

d := time.Second * time.Duration(rand.Intn(5)) / 2

time.Sleep(d)

}

// Notify a task is finished.

wg.Done() // <=> wg.Add(-1)

}

func main() {

log.SetFlags(0)

wg.Add(2) // register two tasks.

go SayGreetings("hi!", 10)

go SayGreetings("hello!", 10)

wg.Wait() // block until all tasks are finished.

}

Run it, we can find that, before the program exits, each of the two new goroutines prints ten greetings.

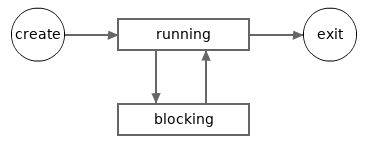

Goroutine States

The last example shows that a live goroutine may stay in (and switch between) two states, running and blocking. In that example, the main goroutine enters the blocking state when the

wg.Wait method is called, and enter running state again when the other two goroutines both finish their respective tasks.

The following picture depicts a possible lifecycle of a goroutine.

Note, a goroutine is still considered to be 'running' if it is asleep (after calling

time.Sleep function) or awaiting the response of a system call or a network connection.

When a new goroutine is created, it will enter the 'running' state automatically. Goroutines can only exit from running state, and never from blocking state. If, for any reason, a goroutine stays in blocking state forever, then it will never exit. Such cases, except some rare ones, should be avoided in concurrent programming.

A blocking goroutine can only be unblocked by an operation made in another goroutine. If all goroutines in a Go program are in blocking state, then all of them will stay in blocking state forever. This can be viewed as an overall deadlock. When this happens in a program, the standard Go runtime will try to crash the program.

The following program will crash, after two seconds:

package main

import (

"sync"

"time"

)

var wg sync.WaitGroup

func main() {

wg.Add(1)

go func() {

time.Sleep(time.Second * 2)

wg.Wait()

}()

wg.Wait()

}

The output:

fatal error: all goroutines are asleep - deadlock! ...

Later, we will learn more operations which will make goroutines enter blocking state.

Goroutine Schedule

Not all goroutines in running state are being executed at a given time. At any given time, the maximum number of goroutines being executed will not exceed the number of logical CPUs available for the current program. We can call the

runtime.NumCPU function to get the number of logical CPUs available for the current program. Each logical CPU can only execute one goroutine at any given time. Go runtime must frequently switch execution contexts between goroutines to let each running goroutine have a chance to execute. This is similar to how operating systems switch execution contexts between OS threads.

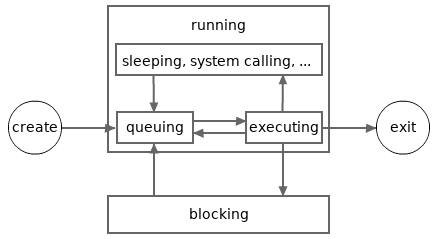

The following picture depicts a more detailed possible lifecycle for a goroutine. In the picture, the running state is divided into several more sub-states. A goroutine in the queuing sub-state is waiting to be executed. A goroutine in the executing sub-state may enter the queuing sub-state again when it has been executed for a while (a very small piece of time).

Please note, for simplicity, the sub-states shown in the above picture will be not mentioned in other articles in Go 101. And again, in Go 101, the sleeping and system calling sub-states are not viewed as sub-states of the blocking state.

The standard Go runtime adopts the M-P-G model to do the goroutine schedule job, where M represents OS threads, P represents logical/virtual processors (not logical CPUs) and G represents goroutines. Most schedule work is made by logical processors (Ps), which act as brokers by attaching goroutines (Gs) to OS threads (Ms). Each OS thread can only be attached to at most one goroutine at any given time, and each goroutine can only be attached to at most one OS thread at any given time. A goroutine can only get executed when it is attached to an OS thread. A goroutine which has been executed for a while will try to detach itself from the corresponding OS thread, so that other running goroutines can have a chance to get attached and executed.

At runtime. we can call the

runtime.GOMAXPROCS function to get and set the number of logical processors (Ps).

The default initial value of

runtime.GOMAXPROCS can also be set through the GOMAXPROCS environment variable.

At any time, the number of goroutines in the executing sub-state is no more than the smaller one of

runtime.NumCPU and runtime.GOMAXPROCS.

Deferred Function Calls

A deferred function call is a function call which follows a

defer keyword. The defer keyword and the deferred function call together form a defer statement. Like goroutine function calls, all the results of the function call (if the called function has return results) must be discarded in the function call statement.

When a defer statement is executed, the deferred function call is not executed immediately. Instead, it is pushed into a defer-call stack maintained by its innermost nesting function call. After a function call

fc(...) returns (but has not fully exited yet) and enters its exiting phase, all the deferred function calls pushed into its defer-call stack will be removed from the defer-call stack and executed, in first-in, last-out order, that is, the reverse of the order in which they were pushed into the defer-call stack. Once all these deferred calls are executed, the function call fc(...) fully exits.

Here is a simple example to show how to use deferred function calls.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

defer fmt.Println("The third line.")

defer fmt.Println("The second line.")

fmt.Println("The first line.")

}

The output:

The first line. The second line. The third line.

Here is another example which is a little more complex. The example will print

0 to 9, each per line, by their natural order.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

defer fmt.Println("9")

fmt.Println("0")

defer fmt.Println("8")

fmt.Println("1")

if false {

defer fmt.Println("not reachable")

}

defer func() {

defer fmt.Println("7")

fmt.Println("3")

defer func() {

fmt.Println("5")

fmt.Println("6")

}()

fmt.Println("4")

}()

fmt.Println("2")

return

defer fmt.Println("not reachable")

}

Deferred Function Calls Can Modify the Named Return Results of Nesting Functions

For example,

package main

import "fmt"

func Triple(n int) (r int) {

defer func() {

r += n // modify the return value

}()

return n + n // <=> r = n + n; return

}

func main() {

fmt.Println(Triple(5)) // 15

}

The Evaluation Moment of the Arguments of Deferred Function Calls

The arguments of a deferred function call are all evaluated at the moment when the corresponding defer statement is executed (a.k.a. when the deferred call is pushed into the defer-call stack). The evaluation results are used when the deferred call is executed later during the existing phase of the surrounding call (the caller of the deferred call).

The expressions within the body of an anonymous function call, whether the call is a general call or a deferred/goroutine call, are evaluated during the anonymous function call is executed.

Here is an example.

// eval-moment.go

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

func() {

var x = 0

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

defer fmt.Println("a:", i + x)

}

x = 10

}()

fmt.Println()

func() {

var x = 0

for i := 0; i < 3; i++ {

defer func() {

fmt.Println("b:", i + x)

}()

}

x = 10

}()

}

Use different Go Toolchain versions to run the code (gotv is a tool used to manage and use multiple coexisting installations of official Go toolchain versions). The outputs:

$ gotv 1.21. run eval-moment.go [Run]: $HOME/.cache/gotv/tag_go1.21.8/bin/go run eval-moment.go a: 2 a: 1 a: 0 b: 13 b: 13 b: 13 $ gotv 1.22. run eval-moment.go [Run]: $HOME/.cache/gotv/tag_go1.22.1/bin/go run eval-moment.go a: 2 a: 1 a: 0 b: 12 b: 11 b: 10

Please note the behavior change caused by the semantic change (of

for loop blocks) made in Go 1.22.

The same argument valuation moment rules also apply to goroutine function calls. The following program will output

123 789.

package main

import "fmt"

import "time"

func main() {

var a = 123

go func(x int) {

time.Sleep(time.Second)

fmt.Println(x, a) // 123 789

}(a)

a = 789

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

}

By the way, it is not a good idea to do synchronizations by using

time.Sleep calls in formal projects. If the program runs on a computer which CPUs are occupied by many other programs running on the computer, the newly created goroutine may never get a chance to execute before the program exits. We should use the concurrency synchronization techniques introduced in the article concurrency synchronization overview to do synchronizations in formal projects.

The Necessity of the Deferred Function Feature

In the above examples, the deferred function calls are not absolutely necessary. However, the deferred function call feature is a necessary feature for the panic and recover mechanism which will be introduced below.

Deferred function calls can also help us write cleaner and more robust code. We can read more code examples that make use of deferred function calls and learn more details on deferred function calls in the article more about deferred functions later. For now, we will explore the importance of deferred functions for panic and recovery.

Panic and Recover

Go doesn't support exception throwing and catching, instead explicit error handling is preferred to use in Go programming. In fact, Go supports an exception throw/catch alike mechanism. The mechanism is called panic/recover.

We can call the built-in

panic function to create a panic to make the current goroutine enter panicking status.

Panicking is another way to make a function return. Once a panic occurs in a function call, the function call returns immediately and enters its exiting phase.

By calling the built-in

recover function in a deferred call, an alive panic in the current goroutine can be removed so that the current goroutine will enter normal calm status again.

If a panicking goroutine exits without being recovered, it will make the whole program crash.

The built-in

panic and recover functions are declared as

func panic(v interface{})

func recover() interface{}

Interface types and values will be explained in the article interfaces in Go later. Here, we just need to know that the blank interface type

interface{} can be viewed as the any type or the Object type in many other languages. In other words, we can pass a value of any type to a panic function call.

The value returned by a

recover function call is the value a panic function call consumed.

The example below shows how to create a panic and how to recover from it.

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

defer func() {

fmt.Println("exit normally.")

}()

fmt.Println("hi!")

defer func() {

v := recover()

fmt.Println("recovered:", v)

}()

panic("bye!")

fmt.Println("unreachable")

}

The output:

hi! recovered: bye! exit normally.

Here is another example which shows a panicking goroutine exits without being recovered. So the whole program crashes.

package main

import (

"fmt"

"time"

)

func main() {

fmt.Println("hi!")

go func() {

time.Sleep(time.Second)

panic(123)

}()

for {

time.Sleep(time.Second)

}

}

The output:

hi! panic: 123 goroutine 5 [running]: ...

Go runtime will create panics for some circumstances, such as dividing an integer by zero. For example,

package main

func main() {

a, b := 1, 0

_ = a/b

}

The output:

panic: runtime error: integer divide by zero goroutine 1 [running]: ...

More runtime panic circumstances will be mentioned in later Go 101 articles.

Generally, panics are used for logic errors, such as careless human errors. Logic errors should never happen at run time. If they happen, there must be bugs in the code. On the other hand, non-logic errors are hard to absolutely avoid at run time. In other words, non-logic errors are errors happening in reality. Such errors should not cause panics and should be explicitly returned and handled properly.

We can learn some panic/recover use cases and more about panic/recover mechanism later.

Some Fatal Errors Are Not Panics and They Are Unrecoverable

For the standard Go compiler, some fatal errors, such as stack overflow and out of memory are not recoverable. Once they occur, program will crash.

The Go 101 project is hosted on GitHub. Welcome to improve Go 101 articles by submitting corrections for all kinds of mistakes, such as typos, grammar errors, wording inaccuracies, description flaws, code bugs and broken links.

The digital versions of this book are available at the following places:

- Leanpub store, $19.99+ (You can get this book from this boundle which also contains 3 other books, with the same price).

- Amazon Kindle store, (unavailable currently).

- Apple Books store, $19.99.

- Google Play store, $19.99.

- Free ebooks, including pdf, epub and azw3 formats.

Tapir, the author of Go 101, has been on writing the Go 101 series books since 2016 July.

New contents will be continually added to the books (and the go101.org website) from time to time.

Tapir is also an indie game developer.

You can also support Go 101 by playing Tapir's games:

Individual donations via PayPal are also welcome.- Color Infection (★★★★★), a physics based original casual puzzle game. 140+ levels.

- Rectangle Pushers (★★★★★), an original casual puzzle game. Two modes, 104+ levels.

- Let's Play With Particles, a casual action original game. Three mini games are included.

Articles in this book:

- About Go 101 - why this book is written.

- Acknowledgments

- An Introduction of Go - why Go is worth learning.

- The Go Toolchain - how to compile and run Go programs.

-

Become Familiar With Go Code

- Introduction of Source Code Elements

- Keywords and Identifiers

- Basic Types and Their Value Literals

- Constants and Variables - also introduces untyped values and type deductions.

- Common Operators - also introduces more type deduction rules.

- Function Declarations and Calls

- Code Packages and Package Imports

- Expressions, Statements and Simple Statements

- Basic Control Flows

- Goroutines, Deferred Function Calls and Panic/Recover

-

Go Type System

- Go Type System Overview - a must read to master Go programming.

- Pointers

- Structs

- Value Parts - to gain a deeper understanding into Go values.

- Arrays, Slices and Maps - first-class citizen container types.

- Strings

- Functions - function types and values, including variadic functions.

- Channels - the Go way to do concurrency synchronizations.

- Methods

- Interfaces - value boxes used to do reflection and polymorphism.

- Type Embedding - type extension in the Go way.

- Type-Unsafe Pointers

- Generics - use and read composite types

- Reflections - the

reflectstandard package.

-

Some Special Topics

- Line Break Rules

- More About Deferred Function Calls

- Some Panic/Recover Use Cases

- Explain Panic/Recover Mechanism in Detail - also explains exiting phases of function calls.

- Code Blocks and Identifier Scopes

- Expression Evaluation Orders

- Value Copy Costs in Go

- Bounds Check Elimination

-

Concurrent Programming

- Concurrency Synchronization Overview

- Channel Use Cases

- How to Gracefully Close Channels

- Other Concurrency Synchronization Techniques - the

syncstandard package. - Atomic Operations - the

sync/atomicstandard package. - Memory Order Guarantees in Go

- Common Concurrent Programming Mistakes

- Memory Related

- Some Summaries