The Go Optimizations 101 and

Go Details & Tips 101 books

have been updated to Go 1.25.

The most cost-effective way to get them is through

this book bundle

in the Leanpub book store.

If you would like to learn some Go details and facts every serveral days, please follow @zigo_101.

Pointers in Go

Although Go absorbs many features from all kinds of other languages, Go is mainly viewed as a C family language. One evidence is Go also supports pointers. Go pointers and C pointers are much similar in many aspects, but there are also some differences between Go pointers and C pointers. This article will list all kinds of concepts and details related to pointers in Go.

Memory Addresses

A memory address means a specific memory location in programming.

Generally, a memory address is stored as an unsigned native (integer) word. The size of a native word is 4 (bytes) on 32-bit architectures and 8 (bytes) on 64-bit architectures. So the theoretical maximum memory space size is 232 bytes, a.k.a. 4GB (1GB == 230 bytes), on 32-bit architectures, and is 264 bytes a.k.a 16EB (1EB == 1024PB, 1PB == 1024TB, 1TB == 1024GB), on 64-bit architectures.

Memory addresses are often represented with hex integer literals, such as

0x1234CDEF.

Value Addresses

The address of a value means the start address of the memory segment occupied by the direct part of the value.

What Are Pointers?

Pointer is one kind of type in Go. A pointer value is used to store a memory address, which is generally the address of another value.

Unlike C language, for safety reason, there are some restrictions made for Go pointers. Please read the following sections for details.

Go Pointer Types and Values

In Go, an unnamed pointer type can be represented with

*T, where T can be an arbitrary type. Type T is called the base type of pointer type *T.

We can declare named pointer types, but generally, it’s not recommended to use named pointer types, for unnamed pointer types have better readabilities.

If the underlying type of a named pointer type is

*T, then the base type of the named pointer type is T.

Two unnamed pointer types with the same base type are the same type.

Example:

*int // An unnamed pointer type whose base type is int.

**int // An unnamed pointer type whose base type is *int.

// Ptr is a named pointer type whose base type is int.

type Ptr *int

// PP is a named pointer type whose base type is Ptr.

type PP *Ptr

Zero values of any pointer types are represented with the predeclared

nil. No addresses are stored in nil pointer values.

A value of a pointer type whose base type is

T can only store the addresses of values of type T.

About the Word "Reference"

In Go 101, the word "reference" indicates a relation. For example, if a pointer value stores the address of another value, then we can say the pointer value (directly) references the other value, and the other value has at least one reference. The uses of the word "reference" in Go 101 are consistent with Go specification.

When a pointer value references another value, we also often say the pointer value points to the other value.

How to Get a Pointer Value and What Are Addressable Values?

There are two ways to get a non-nil pointer value.

-

The built-in

newfunction can be used to allocate memory for a value of any type.new(T)will allocate memory for aTvalue (an anonymous variable) and return the address of theTvalue. The allocated value is a zero value of typeT. The returned address is viewed as a pointer value of type*T. -

We can also take the addresses of values which are addressable in Go. For an addressable value

tof typeT, we can use the expression&tto take the address oft, where&is the operator to take value addresses. The type of&tis viewed as*T.

Generally speaking, an addressable value means a value which is hosted at somewhere in memory. Currently, we just need to know that all variables are addressable, whereas constants, function calls and explicit conversion results are all unaddressable. When a variable is declared, Go runtime will allocate a piece of memory for the variable. The starting address of that piece of memory is the address of the variable.

We will learn other addressable and unaddressable values from other articles later. If you have already been familiar with Go, you can read this summary to get the lists of addressable and unaddressable values in Go.

The next section will show an example on how to get pointer values.

Pointer Dereference

Given a pointer value

p of a pointer type whose base type is T, how can you get the value at the address stored in the pointer (a.k.a., the value being referenced by the pointer)? Just use the expression *p, where * is called dereference operator. *p is called the dereference of pointer p. Pointer dereference is the inverse process of address taking. The result of *p is a value of type T (the base type of the type of p).

Dereferencing a nil pointer causes a runtime panic.

The following program shows some address taking and pointer dereference examples:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

p0 := new(int) // p0 points to a zero int value.

fmt.Println(p0) // (a hex address string)

fmt.Println(*p0) // 0

// x is a copy of the value at

// the address stored in p0.

x := *p0

// Both take the address of x.

// x, *p1 and *p2 represent the same value.

p1, p2 := &x, &x

fmt.Println(p1 == p2) // true

fmt.Println(p0 == p1) // false

p3 := &*p0 // <=> p3 := &(*p0) <=> p3 := p0

// Now, p3 and p0 store the same address.

fmt.Println(p0 == p3) // true

*p0, *p1 = 123, 789

fmt.Println(*p2, x, *p3) // 789 789 123

fmt.Printf("%T, %T \n", *p0, x) // int, int

fmt.Printf("%T, %T \n", p0, p1) // *int, *int

}

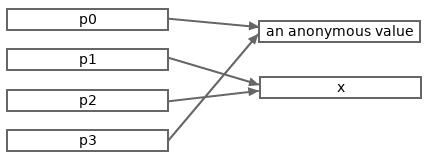

The following picture depicts the relations of the values used in the above program.

Why Do We Need Pointers?

Let's view an example firstly.

package main

import "fmt"

func double(x int) {

x += x

}

func main() {

var a = 3

double(a)

fmt.Println(a) // 3

}

The

double function in the above example is expected to modify the input argument by doubling it. However, it fails. Why? Because all value assignments, including function argument passing, are value copying in Go. What the double function modified is a copy (x) of variable a but not variable a.

One solution to fix the above

double function is let it return the modification result. This solution doesn't always work for all scenarios. The following example shows another solution, by using a pointer parameter.

package main

import "fmt"

func double(x *int) {

*x += *x

x = nil // the line is just for explanation purpose

}

func main() {

var a = 3

double(&a)

fmt.Println(a) // 6

p := &a

double(p)

fmt.Println(a, p == nil) // 12 false

}

We can find that, by changing the parameter to a pointer type, the passed pointer argument

&a and its copy x used in the function body both reference the same value, so the modification on *x is equivalent to a modification on *p, a.k.a., variable a. In other words, the modification in the double function body can be reflected out of the function now.

Surely, the modification of the copy of the passed pointer argument itself still can't be reflected on the passed pointer argument. After the second

double function call, the local pointer p doesn't get modified to nil.

In short, pointers provide indirect ways to access some values. Many languages do not have the concept of pointers. However, pointers are just hidden under other concepts in those languages.

Return Pointers of Local Variables Is Safe in Go

Unlike C language, Go is a language supporting garbage collection, so return the address of a local variable is absolutely safe in Go.

func newInt() *int {

a := 3

return &a

}

Restrictions on Pointers in Go

For safety reasons, Go makes some restrictions to pointers (comparing to pointers in C language). By applying these restrictions, Go keeps the benefits of pointers, and avoids the dangerousness of pointers at the same time.

Go pointer values don't support arithmetic operations

In Go, pointers can't do arithmetic operations. For a pointer

p, p++ and p-2 are both illegal.

If

p is a pointer to a numeric value, compilers will view *p++ is a legal statement and treat it as (*p)++. In other words, the precedence of the pointer dereference operator * is higher than the increment operator ++ and decrement operator --.

Example:

package main

import "fmt"

func main() {

a := int64(5)

p := &a

// The following two lines don't compile.

/*

p++

p = (&a) + 8

*/

*p++

fmt.Println(*p, a) // 6 6

fmt.Println(p == &a) // true

*&a++

*&*&a++

**&p++

*&*p++

fmt.Println(*p, a) // 10 10

}

A pointer value can't be converted to an arbitrary pointer type

In Go, a pointer value of pointer type

T1 can be directly and explicitly converted to another pointer type T2 only if either of the following two conditions is get satisfied.

-

The underlying types of type

T1andT2are identical (ignoring struct tags), in particular if eitherT1andT2is a unnamed type and their underlying types are identical (considering struct tags), then the conversion can be implicit. Struct types and values will be explained in the next article. -

Type

T1andT2are both unnamed pointer types and the underlying types of their base types are identical (ignoring struct tags).

For example, for the below shown pointer types:

type MyInt int64

type Ta *int64

type Tb *MyInt

the following facts exist:

-

values of type

*int64can be implicitly converted to typeTa, and vice versa, for their underlying types are both*int64. -

values of type

*MyIntcan be implicitly converted to typeTb, and vice versa, for their underlying types are both*MyInt. -

values of type

*MyIntcan be explicitly converted to type*int64, and vice versa, for they are both unnamed and the underlying types of their base types are bothint64. -

values of type

Tacan't be directly converted to typeTb, even if explicitly. However, by the just listed first three facts, a valuepaof typeTacan be indirectly converted to typeTbby nesting three explicit conversions,Tb((*MyInt)((*int64)(pa))).

None of these pointer types can be converted to type

*uint64, in any safe ways.

A pointer value can't be compared with values of an arbitrary pointer type

In Go, pointers can be compared with

== and != operators. Two Go pointer values can only be compared if either of the following three conditions are satisfied.

-

The types of the two Go pointers are identical.

-

One pointer value can be implicitly converted to the pointer type of the other. In other words, the underlying types of the two types must be identical and either of the two types of the two Go pointers is an unnamed type.

-

One and only one of the two pointers is represented with the bare (untyped)

nilidentifier.

Example:

package main

func main() {

type MyInt int64

type Ta *int64

type Tb *MyInt

// 4 nil pointers of different types.

var pa0 Ta

var pa1 *int64

var pb0 Tb

var pb1 *MyInt

// The following 6 lines all compile okay.

// The comparison results are all true.

_ = pa0 == pa1

_ = pb0 == pb1

_ = pa0 == nil

_ = pa1 == nil

_ = pb0 == nil

_ = pb1 == nil

// None of the following 3 lines compile ok.

/*

_ = pa0 == pb0

_ = pa1 == pb1

_ = pa0 == Tb(nil)

*/

}

A pointer value can't be assigned to pointer values of other pointer types

The conditions to assign a pointer value to another pointer value are the same as the conditions to compare a pointer value to another pointer value, which are listed above.

It's Possible to Break the Go Pointer Restrictions

As the start of this article has mentioned, the mechanisms (specifically, the

unsafe.Pointer type) provided by the unsafe standard package can be used to break the restrictions made for pointers in Go. The unsafe.Pointer type is like the void* in C. In general the unsafe ways are not recommended to use.

The Go 101 project is hosted on GitHub. Welcome to improve Go 101 articles by submitting corrections for all kinds of mistakes, such as typos, grammar errors, wording inaccuracies, description flaws, code bugs and broken links.

The digital versions of this book are available at the following places:

- Leanpub store, $19.99+ (You can get this book from this boundle which also contains 3 other books, with the same price).

- Amazon Kindle store, (unavailable currently).

- Apple Books store, $19.99.

- Google Play store, $19.99.

- Free ebooks, including pdf, epub and azw3 formats.

Tapir, the author of Go 101, has been on writing the Go 101 series books since 2016 July.

New contents will be continually added to the books (and the go101.org website) from time to time.

Tapir is also an indie game developer.

You can also support Go 101 by playing Tapir's games:

Individual donations via PayPal are also welcome.- Color Infection (★★★★★), a physics based original casual puzzle game. 140+ levels.

- Rectangle Pushers (★★★★★), an original casual puzzle game. Two modes, 104+ levels.

- Let's Play With Particles, a casual action original game. Three mini games are included.

Articles in this book:

- About Go 101 - why this book is written.

- Acknowledgments

- An Introduction of Go - why Go is worth learning.

- The Go Toolchain - how to compile and run Go programs.

-

Become Familiar With Go Code

- Introduction of Source Code Elements

- Keywords and Identifiers

- Basic Types and Their Value Literals

- Constants and Variables - also introduces untyped values and type deductions.

- Common Operators - also introduces more type deduction rules.

- Function Declarations and Calls

- Code Packages and Package Imports

- Expressions, Statements and Simple Statements

- Basic Control Flows

- Goroutines, Deferred Function Calls and Panic/Recover

-

Go Type System

- Go Type System Overview - a must read to master Go programming.

- Pointers

- Structs

- Value Parts - to gain a deeper understanding into Go values.

- Arrays, Slices and Maps - first-class citizen container types.

- Strings

- Functions - function types and values, including variadic functions.

- Channels - the Go way to do concurrency synchronizations.

- Methods

- Interfaces - value boxes used to do reflection and polymorphism.

- Type Embedding - type extension in the Go way.

- Type-Unsafe Pointers

- Generics - use and read composite types

- Reflections - the

reflectstandard package.

-

Some Special Topics

- Line Break Rules

- More About Deferred Function Calls

- Some Panic/Recover Use Cases

- Explain Panic/Recover Mechanism in Detail - also explains exiting phases of function calls.

- Code Blocks and Identifier Scopes

- Expression Evaluation Orders

- Value Copy Costs in Go

- Bounds Check Elimination

-

Concurrent Programming

- Concurrency Synchronization Overview

- Channel Use Cases

- How to Gracefully Close Channels

- Other Concurrency Synchronization Techniques - the

syncstandard package. - Atomic Operations - the

sync/atomicstandard package. - Memory Order Guarantees in Go

- Common Concurrent Programming Mistakes

- Memory Related

- Some Summaries